Lab Book 2014_12_30

Today I

worked on getting a qualitative susceptometer up and running. By qualitative I mean that we won't be attempting

to analyze the returned data to accurately determine any characteristics of the superconducting materials that are to be studied, only the state of the materials,

and the existence, or not of a hysteresis curve for the material.

The why of it all

I’m

experimenting with a quick and dirty susceptometer that can be used with the hray

experiment to determine when we’ve quenched the superconductor. Today’s work is using a ferromagnetic core,

not a superconductor. The responses are

similar and I don’t have to worry about cooling a superconductor.

Experimental Setup

Something old and something new

I’m

pressing a General Radio 1311-A audio oscillator and a Tektronix TDS 210 into

service together.

The general

radio signal generator is being used to drive the coil surrounding the iron

core. The oscilloscope is measuring both

the signal from the General Radio source and the pickup coil on the iron core

as shown below

|

|

Voltage vs. time vs. frequency

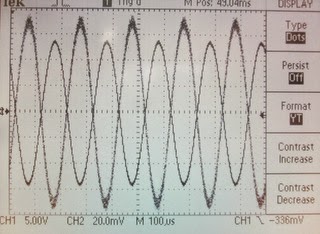

In the

following waveforms, the driving voltage is on channel 1 and the response

voltage from the pickup coil is shown on channel two. Channel one is a cleaner signal than channel

two. There’s a 180 degree phase

difference between the signal just as you’d expect from Lenz’s law and the

output on the pickup coil increases with frequency as you’d expect from Faraday’s

law.

400

Hz

|

500

Hz

|

1000

Hz

|

2000

Hz

|

5000

Hz

|

10000

Hz

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X-Y data

vs. frequency

The expected

hysteresis loop began to appear once the frequency of the generator was brought

sufficiently high. The following data

table illustrates this.

400 Hz

|

|

500 Hz

|

|

1000 Hz

|

|

2000 Hz

|

|

5000 Hz

|

|

10000 Hz

|

The

final data point at 10,000 Hz is shown below with bandwidth limiting on the

scope enabled to cut down on the signal noise:

What we’re seeing

As the

frequency of the oscillator is increased, the loop is opening up because the

ferromagnetic response of the core can’t track quickly enough with the driving

current. Consequently there’s a phase

difference between the two signals and this appears in the x-y display mode as

a gradually opening loop.

It should

be noted that the signal isn’t large enough to cause the iron core to

saturate. If it was, we’d see horizontal

flat extensions at either corner of the loop.

A power amplifier may be added to the arrangement tomorrow to cause saturation.

Here’s a

set of hysteresis curves that depend on frequency[1]. Notice that the enclosed loop becomes wider as

the frequency increases, just as in the data shown above.

How Ferromagnets and

Superconductors are Alike, (well, one way anyway)

I

mentioned that ferromagnets behaved in a similar manner to superconductors when

subjected to a magnetic field. It’s because

their hysteresis curves don’t look too much different. Here’s a hysteresis curve[2] measured for

superconducting Pb. The square is the

theoretically ideal response. The curved

lines are the actual response of the superconductor.

References:

1. Jiles, J.C., “Frequency dependence of

hysteresis curves in conducting magnetic materials

”, Journal

of Applied Physics 76, 5849 (1994) http://dx.doi.org.lib-ezproxy.tamu.edu:2048/10.1063/1.358399

2.

Rjabinin, Shubnikow, “Dependence

of Magnetic Induction on the Magnetic Field in Supraconducting Lead”, Nature,

134, (1934), 286-287

Comments

Post a Comment

Please leave your comments on this topic: