Back in December I posted a picture of the poster that I was taking to the Dallas Astrophysics Symposium. Lots of people asked what it all meant and I promised I’d answer eventually. Well, I've finally found the time to at start expanding on the poster in small chunks. The following is a first attempt and will make far more sense to physicists than it will to anyone else, (at least I hope it’ll make sense to someone).. I’m using these posts as a practice ground for explaining these concepts simply and the explanations should get better as time progresses. In the meantime, thanks for being my practice audience if you decide to read this! If you have questions, please ask them, and if you can see an obviously better way of expressing the ideas, and you’d like to share it that would be awesome and help a lot!

Physicists in the early 1900s defined a quantity called rapidity that serves as a way of measuring how fast a particle is traveling in special relativistic terms. Rapidity itself isn't a velocity, but it can be converted into the velocity of the particle as measured in the laboratory frame using the expression on the first line of picture one below. In the expression, the rapidity is denoted as w. The v to the left of the equal sign denotes the velocity of a particle as measured in the laboratory.

If we rearrange the expression a little bit, we get the second line in the first picture. Then, if we graph the right hand side of the equation, we get picture two. If you take a look, you’ll see that the velocity as measured in the laboratory never gets larger than the speed of light no matter how large the rapidity is. That's kind of nice since it fits with what the theory of special relativity tells us: the velocity of a particle measured in the laboratory frame never exceeds the speed of light.

The hyperbolic trigonometric functions follow similar rules to the more familiar circular trigonometric functions, so I can rewrite the expression in the first picture in the manner shown below in the first line of picture three.

Once I've done that, I can point out that the denominator is actually the ratio of how much time progresses in the lab per time as perceived by the moving particle. This ratio is associated with time dilation. If we look at a graph of the hyperbolic cosine, (picture 4), we see that the ratio can never be less than one and that it can become infinitely large.

Incidentally, the graph shown in picture four in geometric terms is called a catenary. It looks a lot like a parabola, but its not. Catenaries come up frequently in physics and are very interesting in their own right, but I digress, (they’ll turn up again later though… I promise). What this graph tells us is that if we stand still, (have a rapidity of zero), then our time ticks off at the same rate as time in the laboratory. However if we begin to move, even a little bit, laboratory time will tick off more quickly than the time we measure sitting on our moving particle.

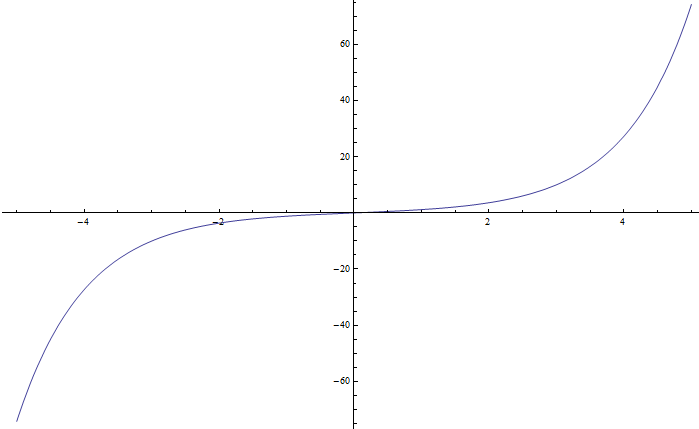

The numerator of the expression in picture three is the rate at which distance traveled in the laboratory changes with respect to time as measured on the moving particle. There’s a really interesting point to be made here. Look at the graph of sinh in picture five. You’ll see that as w increases, the graph moves upwards towards infinity.

While we can’t measure a velocity faster than the speed of light in the laboratory, (see the left hand side of the expression in picture one), but if we measure distance traveled in the laboratory from the perspective of the particle, the result can be as much faster than the speed of light as we please! Does this violate the theory of special relativity? Nope! Special relativity merely says that we can’t measure the speed of a particle in the laboratory to be faster than the velocity of light. Have we known about this right from the start? Yup! If you have access to a university library check out the article by Wolfgang Rindler referenced below where he calculates how many light years a traveler could cover in an average lifetime. The quick answer is “many more light years than the years in the lifetime of the traveler”.

References1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FPhysRev.119.2082

Rindler W. (1960). Hyperbolic Motion in Curved Space Time, Physical Review, 119 (6) 2082-2089. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRev.119.2082

2. Special Relativity by Wolfgang Rindler

http://books.google.com/books?id=8kqBAAAAIAAJ

3. On four velocity

Comments

Post a Comment

Please leave your comments on this topic: